Fuck Patriarchy Day 2022

Graphics by Yeoleum Yun

On the occasion of this year's Fuck-Patriarchy-Day, we dedicate today's post to all the inspiring women whose work and agenda we admire.

We invited some of them to write about the women who significantly influenced their lives, work and thinking.

With contributions from Mire Lee, Annegret Liepold, Charlotte Rohde and Isabelle Tondre.

I'm with her.

Rachel Cusk, Aftermath, Faber & Faber, 2012

The Aftermath of Rachel Cusk, eine Nachlese von Annegret Liepold

Es gibt Autor*innen, von denen bleiben einzelne Zeile hängen, die eine*n nicht mehr loslassen und das eigene Arbeiten verändert zurücklassen. Und es gibt Autor*innen, deren Werke verschlingt man als Ganzes, ohne satt zu werden, man verleibt sich Werk und Autor*in ein, trägt die Satzberge unverdaut mit sich herum. Weil da etwas Unverstandenes ist, ein Rest, von dem man ahnt, dass er bleiben wird.

Ich habe in wenigen Monaten fast alles gelesen, was von Rachel Cusk zu finden ist: A Life's Work: On Becoming a Mother (2001), Aftermath: On Marriage and Separation (2012), ihre Trilogie Outline (2014), Kudos (2016), Transit (2018).

Das ist jetzt drei oder vier Jahre her, aber ich arbeite das ‚aftermath‘ meiner Cusk-Lektüre noch immer auf, lese zusammen, was davon übrig ist. Aftermath – der Titel greift ins Zentrum von Cusk‘ Werk – beschreibt nicht nur die Auswirkungen, den Schauplatz nach dem Krieg, sondern auch das Zurückkehren zu diesem Schauplatz: Nach der Ernte kommt die Nachernte bzw. Nachlese (aftermath): Die Armen lesen zusammen, was auf den Feldern noch übrig ist. Meine Cusk-Lektüre bedarf einer Nachlese, um zu verstehen, was mich so in den Bann gezogen und erschüttert hat, dass ich lesen musste, ohne verstehen zu können. Was ist der Rest?

Der Schauplatz, den Cusk verwüstete und der ein stilles, beinah idyllisches Örtchen war, bevor ich sie las, ist der Feminismus – mein persönlicher Feminismus, der früh begann, ohne dass ich mich Feministin genannt hätte, weil es mir selbstverständlich schien. Als Teenagerin habe ich ‚meine Beauvoir‘ gelesen. La Deuxième Sexe (1949) aber auch viele Romane, Kurzgeschichten, den „Monolog einer gebrochenen Frau“ und es war ja wohl klar: Das wird nicht meine Zukunft sein. Ich dachte, deshalb liest man das, um gewarnt und auf der Hut zu sein. Ich dachte: Mit viel Hut habe ich es selbst in der Hand. An der Uni folgte Judith Butler mit Gender Trouble (1990) und Geschlecht schien keine Rolle mehr zu spielen – es ließ sich mit Worten in Sprache auflösen. Als dann mit Laurie Penny oder Margarete Stokowski eine neue, aus dem eigenen Erfahrungsschatz greifende Generation an Feministinnen aufkam, dachte ich: Pah, da bin ich doch drüber hinweg. Der Diskurs traf mich über die Hintertür, in Gesprächen mit Freundinnen und durch die Lektüre von Rachel Cusk. Outline, der Auftakt ihrer Trilogie, machte mir klar: Ich hatte nicht nur ‚meine Beauvoir‘ falsch gelesen, sondern war in einer Sackgasse gelandet. Mein Denken war männlich, aber mein Körper war der einer Frau und längst all dem ausgesetzt, wovor ich mich hüten wollte – der Hut war eine Illusion, die mich vor der Erkenntnis schützen sollte, dass je länger ich Frau bin, ich desto mehr dazu gemacht werde.

Es gibt Worte, die denken und über die muss man nachdenken. Und es gibt Worte, die handeln, noch während man sie liest. Und es gibt Literatur, die diese Dichotomie von Denken und Handeln aushebelt: Es ist nicht was Cusk über das Mutter- oder (Ehe-)Frausein schreibt, das mir die eigene Sackgasse vor Augen führte, sondern wie: Rachel Cusks Schreiben ist ein Spiel über Bande, das das Ins-Verhältnis-Kommen von Subjekt und Objekt, die Prozesse von Subjektivierung und Objektivierung so ausagiert, dass eine Trennung von Geist und Körper keinen Bestand mehr hat.

In ihren unverblümten Texten zur Mutterschaft oder Scheidung beschreibt Cusk das Frausein und reflektiert es zugleich – in ihrer Trilogie geht sie noch einen Schritt weiter. Hier tritt eine Ich-Erzählerin auf, die nicht sich, sondern die Anderen erzählt. Alles, was wir über sie erfahren, erfahren wir indirekt. Die Erzählerin sagt nicht: Ich heiße Faye, ich bin Mutter, Autorin, geschiedene Frau, sondern wir erleben sie durch das, was in Gesprächen mit ihrem Umfeld zurückgespielt wird: Unser Blick auf die Erzählerin ist der Blick der Anderen. Wir sehen, wie die Welt sie sieht, aber durch ihre Worte. Das Bild, das wir von ihr formen entsteht in der Diskrepanz von fremd und eigen, die sich wie ein Spalt auftut – ein wohl kuratierter Spalt (ein, wie der Titel sagt: Umriss, Outline), denn natürlich behält die Erzählerin die Oberhand. Ganz bewusst wird das erzählende Subjekt hier zum betrachteten Objekt. Enttarnt wird nicht die Erzählerin, sondern die Blicke, die sie treffen – Blicke von Verleger*innen, Veranstalter*innen, Kolleg*innen, deren Begehren, ob weiblich oder männlich, offengelegt wird. Subjekte kreieren Objekte und umgekehrt. Das offen zu legen, darin liegt die Produktivität von Cusks Texten: Sie sind ehrlich, unverfroren, schmerzhaft, abstoßend. So wollen wir die Figur nicht sehen, so wollen wir uns nicht sehen. Und wollen es doch. Das ist der Rest.

Cusks Texte haben meine Lust geweckt, zu einem Zeitpunkt, als ich nur Kopf sein konnte und einen Hut für diesen Kopf gesucht habe, ganz wie ein Gentleman. Aber ich bin eine Frau und trage keine Hüte. Rachel Cusk hat sich die Erlaubnis genommen, ‚Ich‘ zu sagen und – so wie andere Autor*innen, denen man aus Verlegenheit das Label der Autofiktion zuschiebt – das Ich als „Knotenpunkt gesellschaftlicher Kräfte“[1] sichtbar gemacht. Die Lust an Cusks Texten ist die Lust am eigenen Selbst. Sie geben die Erlaubnis, Lust am eigenen Selbst empfinden zu dürfen.

[1]„Entre nous. Ein Briefwechsel über Autofiktion in der Gegenwartsliteratur zwischen Isabelle Graw und Brigitte Weingart“, in: Texte zur Kunst, 2019 (115).

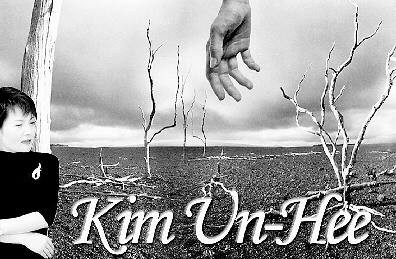

Fan picture of Eon-hee Kim found on the internet

Mire Lee with Kim Eon-Hee

Dear Eonhee

I'm still in the afterglow of our meeting in Jinju. My corona test was negative following a short quarantine, so I was able to catch my flight safely.

When we met, I looked at you more closely, and I was mesmerized by your hands, how young and beautiful they are. After you mentioned spirituality, I thought a little about what a spiritual experience is. I thought that it can simply be something very shocking and intense that shakes one’s existence. After visiting Louis Bourgeois’ house in New York for example, I slept that night with a strong delusional bodily sensation - as if I was wrapped by Louis’ soul. I felt feverish. During our meeting together with Hyosil and Rita, I had a similar sensation. If I can, I want to live only to chase this sensation and taste it over and over again.

This experience is not simply one of ecstasy and joy. Similar to how you said you couldn't sleep thinking about the people who died unfairly and unjustly in the Keyongsang province. You talked about how you were possessed by their fear and pain. In the past, I couldn't project into the pain of others, but at some point, as if artificially, it all started. Half a year after the Sewol ferry sunk, I found myself suddenly transferred to those students trapped in a sinking ship. For days, I was panicking, I was sweating. I cried out to Rita that it was too painful, but she just replied coldly, telling me I was too late.

What I’m trying to say is… after I came back from Jinju, I once again felt my existence had elevated. I realized sharply and painfully, that you are a true poet. Your body and organs fully open to feel and take in everything, only to rupture and tear again, to die again and die anew. As ridiculous as it sounds, I’m crying as I am writing this down because the truth of what I am feeling is so real.

To be a poet is like to be the ultimate metaphor, beating all the other art practitioners somehow. That's why I understood it immediately when you said you are now sick and tired of dividing lines and paragraphs, you are tired of poetry, and that you want to end it soon. When I say you are a real poet, it doesn't mean that you write good poems, but it rather means the complete opposite. Your poems eat up the form, and destroy poetry…

When we had coffee together in Samcheong-dong in 2020, you told me a little about your family history, but I did not know about your mother. I now feel I have a much broader sense of your Family Theater. And also, the more I think about the story of you going to the love motels alone, the more I like it because it reminds me of Isabelle Huppert in The Piano Teacher.

This winter, again, I fell into a mild depression which coloured my time grey… I felt very stressed with the idea of wanting to make my mother happy and be faithful to the fullest before she disappears from this world. I have a work life ahead of me, new people, new places, but I can't control being dragged down by my old world, like gravity. I just want to let go of myself in this warm, heavyweight and slowly sink into a very comfortable death bed.

But at the end of the day, I'm ambitious... so here I am leaving Korea, again and again.

In the taxi coming back from yours, I was holding back my cough and I choked really hard. I took my mask off and I saw my vomit contained in the concave inner part of the mask. I was trying really hard to not get caught by Hyosil and Rita that I threw up. Hyosil and Rita must have been nervous about catching covid but pretended they were calm. It's been a really long time since I hung out with Hyosil properly. I was so moved by how intelligent and adorable she is. She’s an absolute genius!

This is a bit of a ramble that became a homage, but it's my way of letting you know how important you are to me.

Yours,

Mire

Kim Eon-Hee (…) is known as the “Medusa of Korean poetry" for her use of unconventional language, grotesque images, and destruction in various forms in order to continuously shock readers. (…) Through the use of extreme images embodying an overwhelming sense of sacrilege and blasphemy, she evokes an unpleasant and nauseating sentiment. Through this “uncomfortable” poetry, she provides a stimulus for shattering the reader's basic frame of reference, expanding their spectrum of thought, and breaking a consciousness of lies. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kim_Eon_Hee)

Amalia Ulman, Dignity 01, 2017. Photography, 24 x 18 cm. James Fuentes, New York. Courtesy: the artist

Charlotte Rohde with Amalia Ulman

Amalia Ulman contextualized the perversion of my coming-of-age.

In 2011, I started smoking because of tumblr. Tumblr, famous for offering a platform for creating visual escapisms, aestheticised porn and wild fanfiction, works mostly via reblogging. There were relatively few original content creators – a few uploaded other people’s or company's content – but most people filled their personal blogs with content that was circulating. Everyone was anonymous, so even if looking for the source, you wouldn’t know. It was a marketplace of stolen imagery. Nobody seemed to mind.

I followed blogs that I chose for their aesthetic value of being beigy. That was a category, yes; mostly showing fashion, models, interior design, landscapes, cute animals, coffees, flowers, healthy food, designer bags. Skinny women smoking melancholically in windows, gazing into the distant skies. I wanted to be like them; skinny, rich, in control of the aesthetics around me. I wanted my life to be beigy. I was 21.

I am wondering if the need to control aesthetics, and ultimately to use grids is the anorexia of the professionalized teenager. Maybe people who feel out of control become graphic designers. The white page before you substitutes the body you can shape.

So I eventually substituted my body with white pages, and on my way I started a tumblr. Before you are able to control your own body parts, you curate other people’s content to define yourself. Your Self-Image. A projection of your Self that hopefully tells you what you are. If you want to be a good woman, you smoke and melancholically stare out of a window, probably because you are sad, waiting for a man to approach you – but actually not waiting, because you are lost in thought. The male gaze is to be served, but not acknowledged. This ties in perfectly with snow white in her deep sleep waiting for her prince; You need to appear rescuable; we have not come very far my friends.

Because that is what girls do –

They curate themselves.

Amalia Ulman started an instagram performance in 2014 called Excellences & Perfections, in which she performed basic bitch behavior in her instagram account. Next to selfies, a glamorous life in hotels with flowers and champagne, she also posted a lot of inspirational tumblr quotes – in back then hip hand lettering type – stating “Stay pretty. Be educated. Dress well. Get money.” Then her self-written drama turned the main character (herself) into a bad bitch™, posting darker, kinkier aesthetics, sexualising herself, getting a boob job, until she ended with a grand finale, a mental breakdown. The internet loves a pretty girl crying on camera.

Life imitates Art; Art imitates Life. People were really offended when it turned out to be a hoax – but why, you would ask? What is authenticity, a currency? A good performance is a good performance – who cares if it’s on purpose or out of desperate attempts to form a real personality that society might approve. We all just wanna be loved. Who is a „good girl“? Amalia Ulman seemed like one.

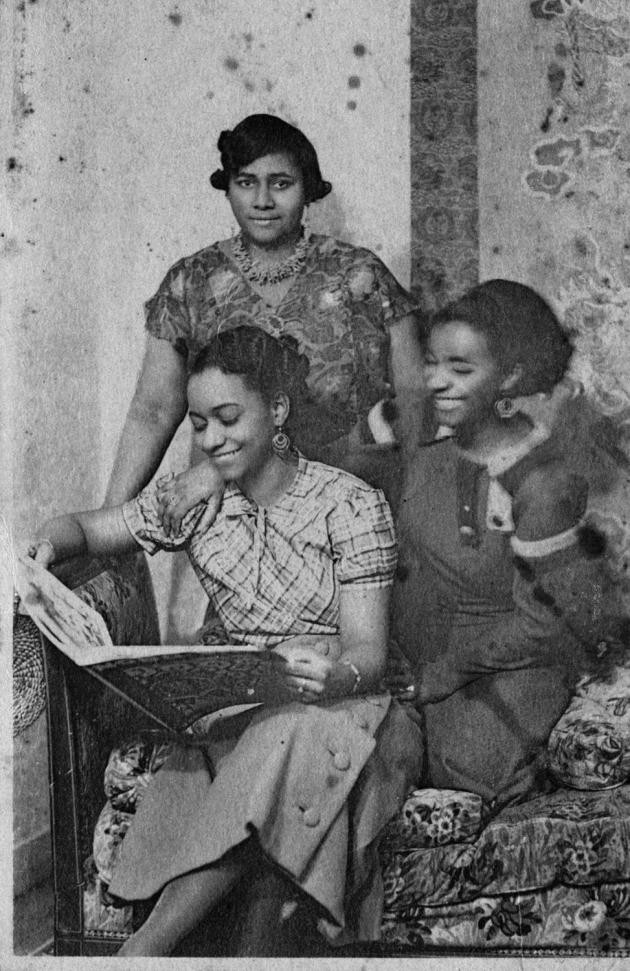

Paulette Nardal (standing), Lucy (left) and Jane (right) in the living room of their apartment at Rue Hébert in Clamart, France. October 19, 1935.

Isabelle Tondre with Jane & Paulette Nardal

Uprooting. A cut, a form of disembodiment, of self-denial that unavoidably came along with the relentless effort to ‘become white.’ This is how Paulette Nardal describes it back in 1932, when it had already long been a feeling but had not yet found a corresponding word to fully address it. Paulette and her younger sibling, Jane Nardal, were both writers and political activists. The two expanded this sense of sisterhood beyond their blood ties to broader commonalities and experiences shared with other French Antillean women who, like them, had traveled from the French Caribbean to Paris between the two world wars. Their weapons were stories, manifests, but also music and especially choirs; writing and singing as means against the entangled oppressions of imperialism, racism, and patriarchy and as invocations of a Race consciousness among the African Diaspora. They had already understood the complexity of intersections, how these could be used as limits against them, but also how they could form a ground for political agency. They began to reconsider the notion of identity as a plural and fluid spectrum, in which ‘to belong’ does not mean to give up on core aspects of oneself but instead to embrace every part. Their writings, many of which overlooked until recent years, were central to the rise of the first Black anticolonial movements in France. ‘L’Internationalisme Noir’ by Jane Nardal (La Dépêche Africaine, 1928) and ‘Éveil de la Conscience de Race’ by Paulette Nardal (La Revue du Monde Noir, 1932) are two examples of such unique writings that were much ahead of their time.