In-Ear Vibrations

OTO Sound Museum

OTO Sound Museum

14–02–2021

by Ben Livne Weitzman

by Ben Livne Weitzman

0:44 - Hair Brushing / 3:14 - Pencil Tapping & Scratching / 4:44 - Bath Sponge Crinkling / 6:14 - Coaster Tapping / 7:14 - Rough Page Flipping / 8:44- Summer Hat Scratching

This list timestamps some of the actions performed by Gibi ASMR in her YouTube video 20 Top ASMR Triggers in 10 Minutes. Coined in 2010, the term ASMR (autonomous sensory meridian response) refers to that orgasmic tingling sensation that prickles around the upper back, the neck, and the scalp when one is met with gentle, auditory, or tactile stimuli, such as whispers or soft touches. Today, there are millions of YouTube videos designed to trigger this sensation with presenters performing such actions as eating KFC wings (44M views), “cooking” Lego bricks (17M), brushing hair (13M), or whispering into a microphone (3M).

ASMR reminds us that hearing and listening are bodily experiences. Sound waves reverb around us and travel through our organs. It is through the physical vibration of our membranes, our eardrums, that these waves are translated into audible sensory data. As Walter Benjamin observed, sound hits “the spectator like a bullet, it happened to him, thus acquiring a tactile quality.”[1] We are moved by sound.

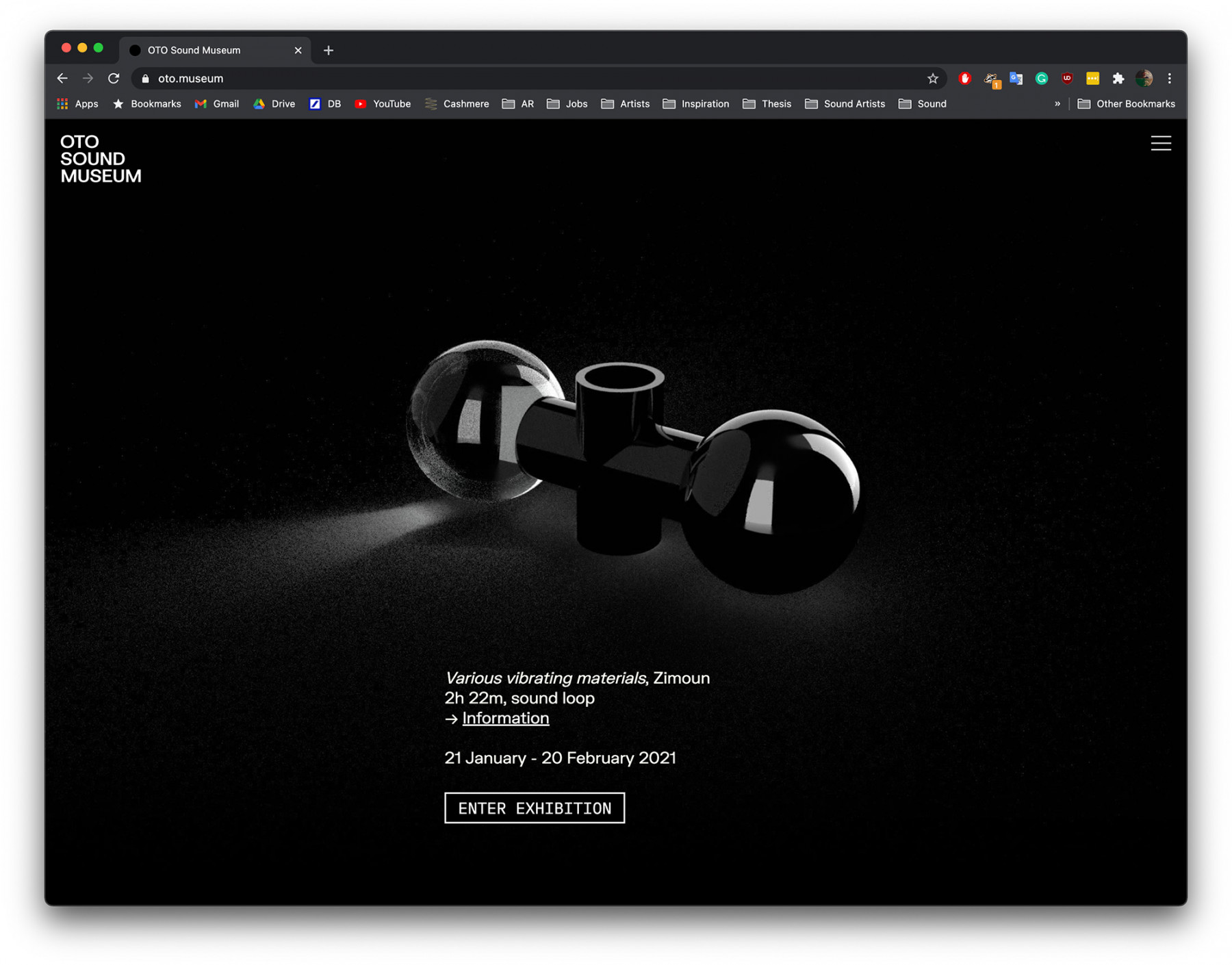

I sit comfortably at my desk when I enter the OTO Sound Museum. Initiated by the curatorial collective Zaira Oram,[2] the virtual museum offers an online sound art collection with a new work being released each month. A dark minimalistic design welcomes the visitor into the ‘exhibition space’ currently featuring the sound piece Various vibrating materials (2020) by Swiss artist Zimoun, mostly known for his large-scale, sound-producing installations. The composition at OTO invites the listener to dive into a collage made up of recordings capturing different vibrating substances.

Tuning in, I was lured into the spatial depth of the piece, generated by the reverb suggesting spaciousness and recurring rhythms of motion. It is hard to avoid the temptation or instinct to superimpose a visual narrative upon abstract audio waves, especially when needing to address them in language afterwards. Being brought up in a society that champions the visual above all other senses, we can find ourselves at a loss when faced with abstract sounds (perhaps not unlike the awkward moment some feel in front of abstract painting). From burned wood cracking in a bonfire to static interruptions in an old telephone line, images of potential sources kept crossing my mind’s eye as I was experiencing the soundscape. At points I found myself outside a club, feeling the walls tremble at the outpouring low-frequency bass sounds. But the seamless transitions and alterations of the piece kept resisting my visual interpretations, holding on to its sonic opacity. In the words of artists and writer Salomé Voegelin: “the spectre of sound unsettles the idea of visual stability and involves us as listeners in the production of an invisible world.”[3]

It was in the early days of the 20th century when sound began to detach itself from music and form an artistic field of its own. The introduction of noise into everyday life with the appearance of machinery was met by Dadaists and Futurists who attempted to appropriate and interact with these new rhythms of the modern Umwelt. In the words of Luigi Russolo, one of the fathers of Futurism, in his 1913 manifesto The Art of Noise: “For years, Beethoven and Wagner have deliciously shaken our hearts. Now we are fed up with them […] We must break at all cost from this restrictive circle of pure sounds and conquer the infinite variety of noise-sounds.”[4]

Ever since, sound art continued to develop in the margins of the art world. Being both ephemeral and invisible, it escaped – or was deprived of – commercialisation and institutionalisation for most of the 20th century. In the mid-90s, however, the so-called “sonic boom” brought sound art to the front of the stage, with exhibitions sprawling across large and small institutions alike. Despite a growing critical recognition, exhibitions of sound art remained somewhat awkward happenings, unavoidably placing visual shackles on an essentially-invisible matter.

With the current shutdown of all physical, communal spaces, the art world desperately tries to find ways in which to meaningfully inhabit the cyberspace. The OTO Sound Museum, with its focus on invisible, ephemeral, sonic-scapes, offers more than a temporary band-aid for a time of crisis. With its visually reduced design and browser-based accessibility, the OTO Sound Museum manages to bring sound works close to the listeners without “visualising” them, as is so often the case in classical exhibition settings. David Toop, who curated the influential show ‘Sonic Boom: The Art of Sound’ in London’s Hayward Gallery in 2000, referred to sound art as essentially “homeless”, as it does not fit in any of the existing models for exhibiting art.[5] Virtual spaces like the OTO Sound Museum suggest a home without walls, in which sound art could resonant without being constrained to a visual environment.

[1] Benjamin, Walter: ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’ Illuminations: Essays and Reflections. By Walter Benjamin. Trans. Harry Zohn. Ed. Hannah Arendt. New York: Schocken, 1969, p. 217-51. 238

[2] The curatorial collective Zaira Oram consists of Francesca Ceccherini, Eleonora Stassi, Chloé Dall’Olio, and Camille Regli.

[3] Voegelin, Salomé: Listening to Noise and Silence: Towards a Philosophy of Sound Art. London: Bloomsbury, 2013. 12

[4] Russolo, Luigi: The Art of Noise: (Futurist Manifesto, 1913). Trans. Robert Filliou. New York: Something Else, 1967. 6

[5] Toop, David, and Christian Marclay: ‘Conversations in the Archive: Sonic Boom: The Art of Sound (2000).‘ Southbank Centre. Hayward Gallery. Web. 06 Jan. 2019

Zimoun – Various vibrating materials

21 January – 20 February

OTO Sound Museum