Sarah Rapson

Secession, Vienna

by Robin Waart

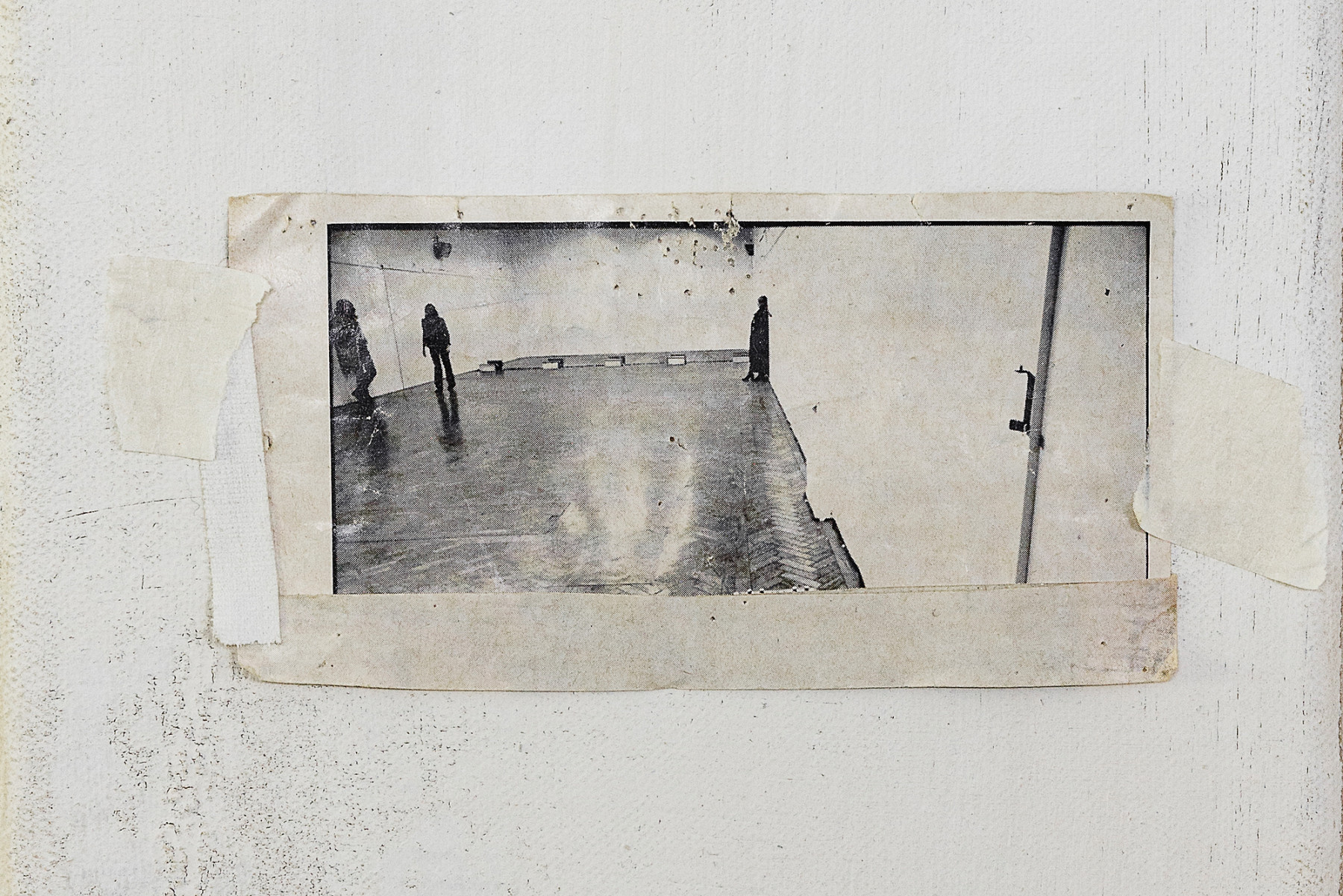

Installation view, Sarah Rapson, Ode to Psyche, Secession, Vienna, 2021. Photography: Manuel Carreon Lopez

Sarah Rapson’s art is one of rehearsal. To say that she is a ‘practising’ artist captures an aspect of her work most resilient in each of the exhibitions she has had since resurfacing as an artist who exhibits, with the gallery solo Sell the House at New York’s Essex Street in 2019, the inaugural group show EDITORIAL at the Macro Museo in Rome the year after, followed by Tiny Trip at Modern Art in London, also 2020. Last November, Ode to Psyche opened at the Secession in Vienna. Rapson’s installation expands across three consecutive rooms, including a video work, a sequence of diptychs and triptychs and single paintings, presented alongside printed pieces, crumpled and pinhole(d) cutouts, declarations and annotations, displayed in vitrines or pasted onto the wall. There is language everywhere, highly specific yet equally elusive. Quotations from books, magazines, a newspaper art review, captions, words written on the backside of photo clippings, at points covered, painted over, glued to the outer sides of the canvases. We are all on the outside of something. In Rapson’s work, the outside is as much about doubt as it is a decision, a mediation between inside(r) and outside(r) art. It is hard to find a better place to be stuck in.

Installation view, Sarah Rapson, Ode to Psyche, Secession, Vienna, 2021. Photo Pascal Petignat

The exhibition is spread across three rooms in the basement galleries of the building:

Room 1: film, checklists and words on paper in two plexiglass wall mounts. Sound on. Lights off.

Room 2: three vitrines, roughly taped close, two with, one without glass filled with sketches, stacks of papers in different sizes; a small rectangular canvas with a clipping taped onto the wall right under it, as if it were sliding down (Love is everywhere (a British artist), 2021); a fourth sealed vitrine with five paintings, another photo clipping on top. Some pieces of the fibre tape remain on the walls, as do two identical photographs titled Performance Tent\Performance Tent (2021), differently folded and pin-perforated in the doorway between the second and third room. Fluorescent tube lights, spot on.

Room 3: twenty-five paintings, in constellations of two, three, but also single. Beige, white, black, monochromatic (paintings of almost nothing). Nails are hammered here and there into the wall near several of the canvases, exposed, naked, holding nothing but themselves. Two old brown leather benches from the Leopold Museum, abrased, one mended with a piece of tape. In the back, at the end of this room, the two-part triptych Don Juan New York 20th century (2021) stands out in material diversity: “soot, calico, paint, printed matter, hessian, linen, wood” for the first and “oil, canvas, printed matters” for the second three elements. As paintings, they are very vertical, upright – seemingly straight from afar, up close, they appear oddly bent. The only light source here is natural, entering through the high horizontal windows, sending in streaks of bright sunshine across the canvases. When the winter sun sets, yellow and red street lights softly sway around the space, obscuring its contents.

Sarah Rapson, galerie galerie/ session, 2021 (Video, 1:33 min). Ode to Psyche, Secession, Vienna, 2021. Photography: Pascal Petignat

Besides the new paintings and the older White Flower (private collection) and romantic art forum, both from 2007, Ode to Psyche builds on ongoing, unfinished works. This becomes clear in the first of the three spaces, where galerie galerie/ session (2021) keeps playing––a looped video of Rapson walking along a heavily trafficked Viennese road, shot on super eight films just before the exhibition’s opening. The footage is fuzed with clips of black-and-white paintings from her Instagram account and excerpts of recordings from the early 2000s, where she can be seen moving along a rocky coastline, lugging and filling a suitcase with sand; entering and reentering a tent; walking up to and stepping into what seems to be an art gallery. [1]

That is much commotion for a one and a half minute video. Without a storyline or colour and with changing music in the background: one of Glenn Gould’s English Suites, a dramatic violin crescendo, grimy unidentified pop, guitar, drums, vocals (David Bowie?). Changing ratios, resolutions, and qualities sampled together with short moments of silence, like memories flashing by, almost too fast to remember. Their rhythm, sound and noise bleed into the ensuing galleries and introduce Rapson’s work as what it is: diachronic, processual, layered and re-covered. Now and then. Here and there.

Sarah Rapson, Nonchalant/ cart, 2021. Oil paint and plaster on linen, lead pain and printed matter on linen, nails. Photography: Manuel Carreon Lopez

In contrast to the moving image’s hectic pace stands the slowness of the paintings in the third gallery, whose fading palette seems to copy the coming and going of the daylight it is exposed by. Evidencing other, rejected hangings, the barren nails on the walls beside the canvases imply progress in the opposite direction, confessionally sticking out. “The nails are the truth of the situation”, as Rapson has said. [2]

But which/what truth? While making the final hanging less final, this truthful situation is also but one scenario, where unrealised options are presented as still possible. A provisionality of some kind is also present in the bits of tape stranded in different places across the exhibition. Accurate pointers to a linear process of moving something; the nails could also indicate where to put the paintings back again.

Sarah Rapson, 3 standing vitrines, 2021. Printed matter, transcripts and ink on paper, vitrine. Dimensions variable. Ode to Psyche, Secession Vienna, 2021. Photography: Manuel Carreon Lopez

Meaning: ‘The truth in painting’ (to go with the title of Jacques Derrida’s book from 1978, based on Paul Cézanne’s statement “I owe you the truth in painting”) might reside not in-, but outside of it. Elsewhere. Concretely, in this case, ‘elsewhere’ is the downstairs men’s lavatory, where Lyre (2021) is playing: a looped recording of Rapson singing over and over the same four lines from The Doors’ Light My Fire (1967), as she emphatically sands the surface of her paintings:

You know that it would be untrue

You know that I would be a liar

If I was to say to you

Girl, we couldn’t get much higher.

These lyrics recur in the description for the exhibition catalogue that takes the form of a ‘matchbook’. There, the Girl in this refrain has become a Man, engendering a more flexible truth and, unavoidably, conflating the title’s Lyre with a more lyrical ‘liar’. The sound piece also follows the much earlier Poetry reading / from a cassette audio tape recording made while climbing the east cliffs at west bay in england (2005) in which Rapson begins reciting ‘A thing of beauty is a joy forever’ from John Keats’ Endymion while climbing a cliff, from memory, panting heavily (perusable online on the Macro Museo’s website). [3]

Sarah Rapson, Trip, 2021. Oil paint, printed matter and tape on canvas, paint over stained canvas, oil paint on linen, nails. Photography: Manuel Carreon Lopez

Elsewhere is where the paratextual qualities of Rapson’s work come out. Away from the centre, outside the galleries, along the margins and edges of the canvas, where the history of their making is revealed. “Gothic Renaissance Eighteenth Century”, exploding into snippets of designation, on one side of the Don Juan New York 20th century (2021) canvases, like the spine of a book. On another side, the clippings she selected and leaves uncovered depict the lines, vertical and horizontal, that separate image from text – mindful of the wraparounds Jo Baer used to paint. When, as in one of these, the black and white photographs, excised from a catalogue or magazine, are attached (stuck, pinned, gessoed, plastered) to the painted surface, its plane is reconfigured, making it a frame itself.

arah Rapson, Vitrine, 2021. Wood pigment, roman earth, black oil paint, sand oil paint, newspaper, printed matter, ink on paper, ink, tape, vitrine. Dimensions variable. Detail. As part of Ode to Psyche, Secession Vienna, 2021. Photo Manuel Carreon Lopez

Not done with, is how these clippings and cutouts look, many of them individually (sub)titled Love is Everywhere: as if they had lived in someone’s pocket. Like the photos of loved ones we carry around with us, they have the capacity to move, from one situation to another, from the canvas to the wall.

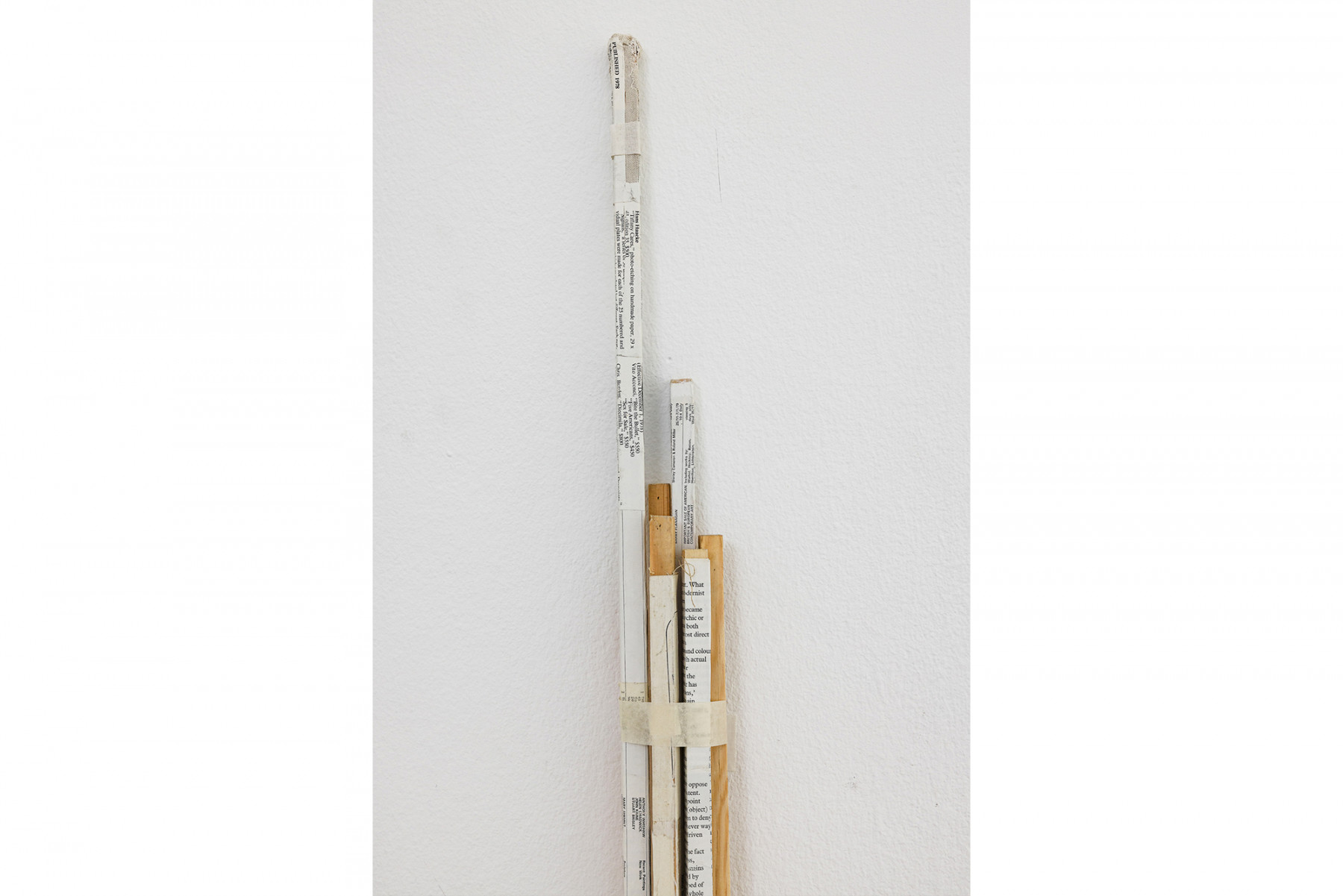

In Oracle stick (2021), also in the third room, on the far opposite of the Don Juan piece, Rapson takes this strategy of quotation (and perambulation) even further: made of pages and parts of pages, text-only, wrapped and glued around several wooden bars, exposing fragments of once coherent sentences, legends, names, places, a price list. “Published 1978”, “will be devoted to Women’s”, “Hans Haacke”, “Rome,” ending on a comma.

The fact that the names of the artists, artworks, and art spaces in the photographs and cutouts usually remain unidentified, even unidentifiable, is not a problem, nor is it an omission. It is a structure, and it is a choice. To not give away your sources but rather repeat the image again and again like the trope it is. Rapson, quoting Slavoj Žižek, has stretched this repetition: into a “melancholic[’s] stratagem: the only way to possess an object, which we never had, which was from the very outset lost, is to treat an object that we still fully possess, as if this object is already lost.” [4]

Sarah Rapson, Oracle stick, 2021. Printed matter and tape on wood. Detail. Photo Manuel Carreon Lopez

However, also when a text can be traced, when the “the hell that is being an artist” on the side of one of the small canvases in Vitrine (2021) can be completed, what is confirmed is not the source of the newspaper clipping, [5] but Rapson’s self-criticism and her humour – as a method of survival. Crucially, this investment in what it can mean to be an artist is expressed most funnily and devastatingly in the first vitrine: an untitled, undated text piece starting on “Ox on the Cliff at Pourville, Clear Weather”, running over three sheets of fading paper that slowly turn into a crescendo of (a)typical art reviews, show descriptions, interrupted now and then by + signs. Somewhere in the middle of the second sheet, from a 2002 review of Gerhard Richter’s 40 Years of Painting at MoMA, this paragraph appears:

But beauty is still out there. We can see it only if we don’t lie to ourselves. It’s what is left after you strip away clichés & false rhetoric. ‘I constantly despair at my own possibility of ever accomplishing anything, of painting a valid, true picture or even knowing what such a thing ought to look like,’ he once wrote ‘But then I always have the hope that, if I persevere, it might one day happen.’ Clearly it does happen in the show. + too good to be true. [6]

Mixing Richter’s doubt and his belief with the reviewer’s enthusiasm, the phrase + too good to be true is marked by the + as Rapson’s – as if her own voice is a footnote. Indeed, the denseness of her own show, over twenty years of (not-)painting, does have something of a collection of notes that together make for one body of work.

Sarah Rapson, Untitled, three-volume matchbook catalogue for Ode to Psyche. Secession Vienna. 2021. Photography: Natascha Unkart / belle & sass

The titles given to this body of work range widely, but when Rapson continues the cutout series Love is everywhere and names individual works at the Secession Vienna shit (diptych) or stuck on earth – bloccato sulla terra, these descriptive denominations are attempts to, well, lighten up and cut the crap. That is probably just how the psyche should be addressed, sung to. An ode is also an appeal, a call – to get there, wherever it is that you aren’t in yet. To recite the opening lines of Endymion, to (re)enter again and again, whether it is into a tent, a gallery, or the art world. Repetition, rehearsal, is one way to halt the paralysing, all too critical counterpart of self-reflection. To work-around and work-with these extremes of giving up or going on that preoccupy Rapson’s practice. Between soft images and hard references, from painting to print, entirely textual to absolute texture, and to round it off, by devising a book one cannot read. Instead, the three-volume catalogue/matchbox publication is meant to burn: to light the gas, a candle, your cigarettes, burn your paintings, or, simply, light your fire.

Sarah Rapson - Ode to Psyche

20.11.2021 - 20.02.2022

Secession

Friedrichstraße 12

1010 Vienna, Austria

[1] As always in these performances, Rapson can be recognized by the white pants and black shirt she wears.

[2] Sarah Rapson, during a walk-through of the exhibition for the opening on November 19, 2021.

[3] Something maybe only Richard Aldrich has done by pasting a slide onto his canvases.

[4] Meet the artist: Sarah Rapson, Macro Museo (2021). The quote, recited in the meet-the-artist, where the words are nearly indistinguishable as Žižek’s, is from his ‘Melancholy and the Act’ in Critical Inquiry 26 (Summer 2000), p. 661; reprinted in Did Somebody Say Totalitarianism? (London and New York: Verso, 2001), p. 146

[5] “or maybe just the hell that was being Philip Guston”, Roberta Smith, ‘After the Storm – Philip Guston for Real’, The New York Times, September 9, 2021

[6] Michael Kimmelman, ‘Gerhard Richter: 40 Years of Painting’, The New York Times, April 19, 2002 (Rapson slightly changed some of the interpunction in Kimmelman’s text)