Zuzanna Czebatul and Jobst Meyer

Exile Gallery, Vienna

by Domen Ograjenšek

Zuzanna Czebatul and Jobst Meyer. Installation view. Monument Error, 2022, EXILE Gallery, Vienna. Photogarphy: Christian Siekmeier.

Monument Error threads its own insistent hauntology.

Not far from Vienna's Exile Gallery, under the careful vigil of some conifers and neatly cut shrubbery, stands the bust of the poet Josef Weinheber, once one of the most-read poets in Nazi Germany. The monument can be easily overlooked. Blink twice while strolling through the park and you’ll surely miss it. Despite its subtle physical appearance, the mere symbolic presence of the memorial has been the cause of persistent conflict. The bust was erected in 1975 and has since then been the target of repeated acts of anonymous vandalism. This led to the fortification of the memorial with an underground concrete foundation in 1990. However, in 2013, the foundation itself was uncovered and exposed as part of an unauthorised artistic intervention, aiming to highlight the tension surrounding the memorial.

The exposed concrete made the tension tangible. All that was soft and pliable has been determinately dug out so that only the persistent material backbone of the desire to keep the burst standing remained, resisting the eroding powers of its opposition. The monument now seems even taller, leaner. Its concrete foundation burrows into the surrounding soil as if the construction could somehow expand endlessly downwards towards the secluded Earth’s core, firmly securing the elevated bust in its flight from its material ground into our collective consciousness.

Zuzanna Czebatul: Untitled, 2022. Mixed media, 48x77x80 cm. Monument Error, 2022. EXILE Gallery, Vienna. Photogarphy: Christian Siekmeier.

These are the spectral vectors of persistent past that the exhibition takes advantage of as the Vienna-born poet finds himself embedded in Untitled (2022) by Zuzanna Czebatul. Using a digital 3D printing process, the artist produces a low-tech replica of the local memorial. The artwork mimics the original, imitating, for instance, its metal patina, yet presents it on an exaggerated, flattened platform that heavily diverges from the source material. The platform resembles a splatter, is slightly raised from the ground, and appears as nearly floating. It is rebelliously horizontal, daringly flat – subverting the very vectorial constitution of the original. With it the air of eerie disinterestedness of the expanding memorial (burrowing, elongating, traversing ever more swiftly into our collective mind) all but disperses so that eventually only mischievous nonsensicality remains in its stead.

What gives the spectre ground to appear is taken away with the reproduction. The rug pulled from under Weinheber’s chin, so to say. Even only to make it reappear elsewhere. In another form, under different conditions. As a side product of the rendering process for Czebatul’s work, a blurry image of Weinheber becomes the exhibit’s access point. The figure accompanies the deserted structures and landscapes of Jobst Meyer’s paintings and the ominous hanging pillars of Czebatul’s Columns of Empire (2021) as a figure that is out of place, an invisible ghost, whose ambivalent presence leads one to reexamine the status of the public persona on display, alongside the systemic doctrines that keep it in its place even after its time has seemingly all but passed.

~

The calmness of shifting sands, of the dragging tarp in wait of wounded flesh, imbues the scenes of Job Meyer’s large-scale paintings with a vacuous quality. Action is hinted at as something that has already passed, is yet to occur, or by some strange reason is unfolding remotely, at a distance, dislocated from the immediate scene. The colours are muted and eerily flat, disturbed only by the soft granulated textures of the sand and tarp, an occasional sharp edge of a shovel or a scythe, or the prominent emblem of a red cross. If there is an event that could take place in such still scenery, it is traceable merely in the faint juxtaposition of the granulated fuzziness and the sporadic sharpness of the image. Sharpness persists where function or “handiness” of the depicted objects remains despite the seemingly unlikely nature of them being of use or used, at an inconspicuous edge of a tool or a sign, leading one to think that the scale of the hinted calamity or armed conflict has somehow shifted and the latter now take place on the level of minuscule surface tensions instead.

Jobst Meyer: Zelt, Kreuzfahne und Sicheln, 1973. Tempera on canvas, 175x200 cm. Monument Error, 2022. EXILE Gallery, Vienna. Photogarphy: Christian Siekmeier.

Picture a drop of water. The surface tension draws in, compacts: unity is upheld with utmost necessity, pulling in surface molecules into the rest of the liquid, diverging the path of movement, at times even halting it completely. The spherical shape of a drop or a bubble is riddled with morphological duality. Within, time stands still (change comes only by vaporisation or a sudden burst), inscribing it with a sense of gridlock or stagnation; whereas outside, the tense surface serves rather as a medium of movement, even accelerating propulsion. The tension that immobilises can propel that which can resist its molecular pull. In other words, the moment that on first glance presents itself as the barring of futurity, the very halting of time and history, might in its vacuous emptying (the barring of the event) propel us across the surface of contemporaneity, in effect catapulting us out of our perspective/existential gridlock.

Surface tension might not be the proper descriptor, yet it is able to capture one of the more elusive features of Meyer’s work: the flattened patches of colour that remove any trace of airiness from the image, depicting even the very sky as viscous and thick. Air stands motionless, swallowing the objects, pushing against their surface boundaries. So much so that the sharp edges become standalone figures – converging in a spiral fashion into the infinitesimally fuzzy monochrome.

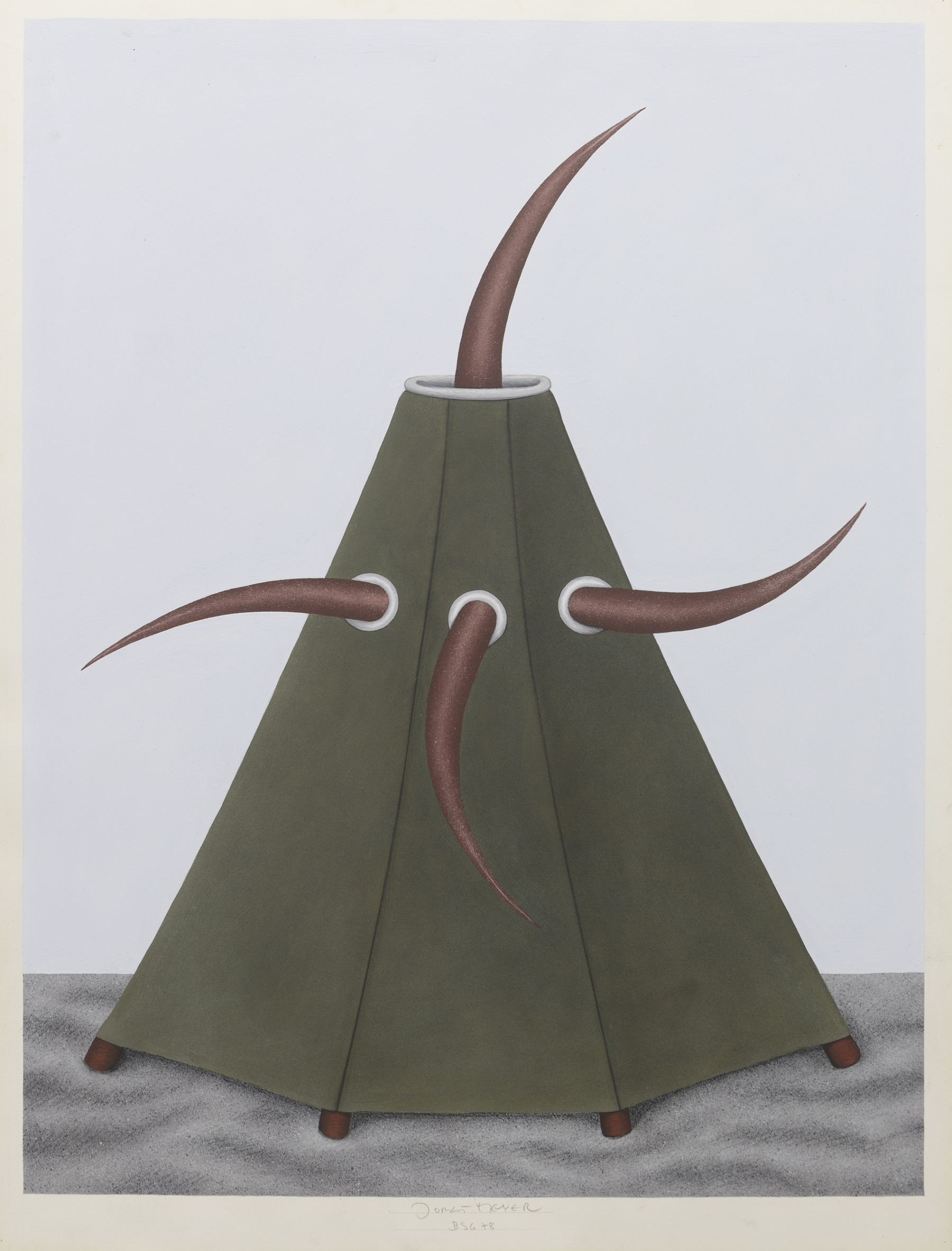

Jobst Meyer: Untitled, 1977/8. Tempera and crayon on paper, 88x67 cm (each). Monument Error, 2022. EXILE Gallery, Vienna. Photogarphy: Christian Siekmeier.

This characteristic is repeated and further developed in the series of untitled works from 1977/8. What were still recognisable objects (a tent, a shovel, the emblem of the red cross) in the exhibited works from ’73 are here congealed into unrecognisable, speculative structures that have all but exchanged the pragmatics of function or “handiness” for the enigmatic allure of the sharp edge or a spike. The entire structure seemingly emerges as an organic side effect of its aesthetic principles. The structures are still depicted as occupying a barren, sand-filled landscape, nondescript and void-like. However, the meaning of their presence, of them being there, is all but lost. If the emblem bearing tents of the works from ’73 could be perceived as occupying a calamity stricken scene, the structures from ’77/8 lack such discernible context. The space they occupy is rather a “non-space” or a vortical space of sinking sense, where reason wades into the impenetrable mundanity of stillness, seeping through the pictorial space into what could be deemed its own mimetic underground.

As the sharp edges as figures morph in standalone speculative structures, the works begin to express a certain gothic sensibility, not unlike what Ruskin ascribed to the gothic ornament in the Stones of Venice:

“[…] the Gothic ornament stands out in prickly independence, and frosty fortitude, jutting into crockets, and freezing into pinnacles; here starting up into a monster, there germinating into a blossom; anon knitting itself into a branch, alternately thorny, bossy, and bristly, or writhed into every form of nervous entanglement; but, even when most graceful, never for an instant languid, always quickset; erring, if at all, ever on the side of brusquerie.” [1]

Jobst Meyer: Untitled, 1978. Tempera and crayon on paper, 88x67 cm. Monument Error, 2022. EXILE Gallery, Vienna. Photogarphy: Christian Siekmeier.

Jobst Meyer: Untitled, 1978. Tempera and crayon on paper, 88x67 cm. Monument Error, 2022. EXILE Gallery, Vienna. Photogarphy: Christian Siekmeier.

The thorn-like protrusions of these structures can be seen taking on the “active rigidity” of the Gothic rib, evading the pragmatics of function and reaching beyond their grounded foundations, elongating ever further towards the vacuous sky [2]. As mentioned before, the structures in the works form ’77/8 seem more like organic side-effects of the figures’ aesthetic principles than standalone objects defined by a pragmatic function. They adopt the re-orienting tendency of the gothic style, abandoning the traumatics of earth and soil for the ephemerality of the sky (its light and air), yet not without messing it up a bit in the process. The gothic tendency gains an almost disorienting quality in Meyer’s works, as the oppositional duality of ground and sky is all but muddied (the sky depicted as muted and viscous, while the ground ephemeral and grainy), causing the thorn-like protrusions to extend in various, what might even be random, directions, sharpening and in some cases curving into mundane nothingness – their threatening infinitesimal tips.

One could say that these speculative features express a rather nihilistic take on (architectural) structures. They question what it means for something to be man-made or not, organic or inorganic, to be of use or bear a function, or in the extreme case be completely devoid of any of it. They even question the implicit value of such demarcation — venturing ever further towards the dark side of meaning formation and valuation processes, into what could be deemed the violent undercurrent of reason and sense.

Zuzanna Czebatul: Columns of Empire, 2021. Mixed media, 180x60x60 cm (each). Monument Error, 2022. EXILE Gallery, Vienna. Photogarphy: Christian Siekmeier.

This is reflected in and further emphasised by Zuzanna Czebatul’s Columns of Empire (2021), exhibited in the direct vicinity of Meyer’s works from ’73. If Meyer’s protrusions are dedicated to the infinitesimal topologic puncturing, Czebatul’s columns highlight the violent pull of a protective film instead. The mat black columns hang ominously in the centre of the gallery. Suspended from the ceiling by metal chains, they appear as spectral architectural elements as much as somewhat twisted punching bags. Their artificial “prickly independence” (sleek notches, threatening curvatures, and sporadic patches of synthetic fabric and rough Velcro-like fibres) manifests the bubbling violence and innate aggression of order, stifling social progress and suppressing any source of will that would fail to seek shelter in its impenetrable dark interior. No technics required; their unapologetic suppression achieved on the level of form itself (taking advantage of the morphological duality of surface tension to deliver on its final weaponised form).

Albeit bleak, what the columns indicate is that passivity can be weaponised. The columns are as much obstacles as they are weapons. The appropriated shapes of what is supposedly anti-riot gear repel the thought of tactile encounter, while also eerily luring one’s limbs, pulling one into collision with the black mass, into a fight that they surely cannot win. In effect, immobilising them. One does not need to experience such an encounter to realise what could be the outcome. The patterning of the notches, curvatures, and fibres reads as a rather familiar language, addressing one’s brute and grimy innards (that sense of conviction, often described as coming from the gut), warning one that resistance is futile. But as much as the columns indicate that passivity can be weaponised “against” one, they also indicate that it can be weaponised “for” one, on one’s behalf.

Zuzanna Czebatul and Jobst Meyer. Installation view. Monument Error, 2022. EXILE Gallery, Vienna. Photogarphy: Christian Siekmeier.

The tension that immobilises can propel that which can resist its molecular pull. While it could, indeed, be said that the features in Meyer’s and Czebatul’s works express a rather nihilistic take on (architectural) structures, it could also be said that darkness is not necessarily less instructive than conventional values of life and enlightenment [3]; that the lessons that powerlessness and passivity hold might still prove to be of value. Monuments cast shadows and columns of empires eclipse the very sun, yet we still fail to grasp all that is possible when light ceases to be the sole principle that guides and shapes our every move.

Monument Error

Zuzanna Czebatul and Jobst Meyer

27/01 – 5/03/2022

EXILE Gallery

Elisabethstraße 24

1010 Vienna, Austria

[1] John Ruskin, 1860, Stones of Venice: The Sea-Stories, New York: Yohn Wiley.

[2] Lars Spuybroek, ‘Gothic Ontology and Sympathy: Moving Away from the Fold’, in: Sjoerd van Tuinen (ed.), 2017, Speculative Art Histories: Analysis at the Limits, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

[3] Gilda Wiliams (ed.), 2007, The Gothic, London & Cambridge (MA): Whitechapel & MIT Press.