James Gregory Atkinson

Dortmunder Kunstverein

by Paula Kommoss

James Gregory Atkinson, CST/CET Office, 2021, Installation View (Detail) Dortmunder Kunstverein, 2021, Photo: Jens Franke

Two clocks are displayed at the threshold of James Gregory Atkinson’s solo exhibition 6 Friedberg-Chicago at the Dortmunder Kunstverein. One follows Central European Time, the local German time and the other the Central Standard time, in Chicago, Illinois. The time difference and the constant ticking visualise a part of Germany's history and its relationship to Black soldiers that is irreversibly tied to the presence of US American soldiers on the ground in Europe, especially since the end of World War II. With an extensive collaborative archive at its centre, this exhibition renders manifolds of documents, books and personal notes, enabling a historical contextualisation while re-tracing the many entangled complexities through Atkinson's personal history. Atkinson's father, born in Chicago, was one of many African-American soldiers sent to Germany. He was stationed at the US Army station Ray Barracks in Friedberg at the beginning of the 1980s. Here in Germany, he met Atkinson’s mother.

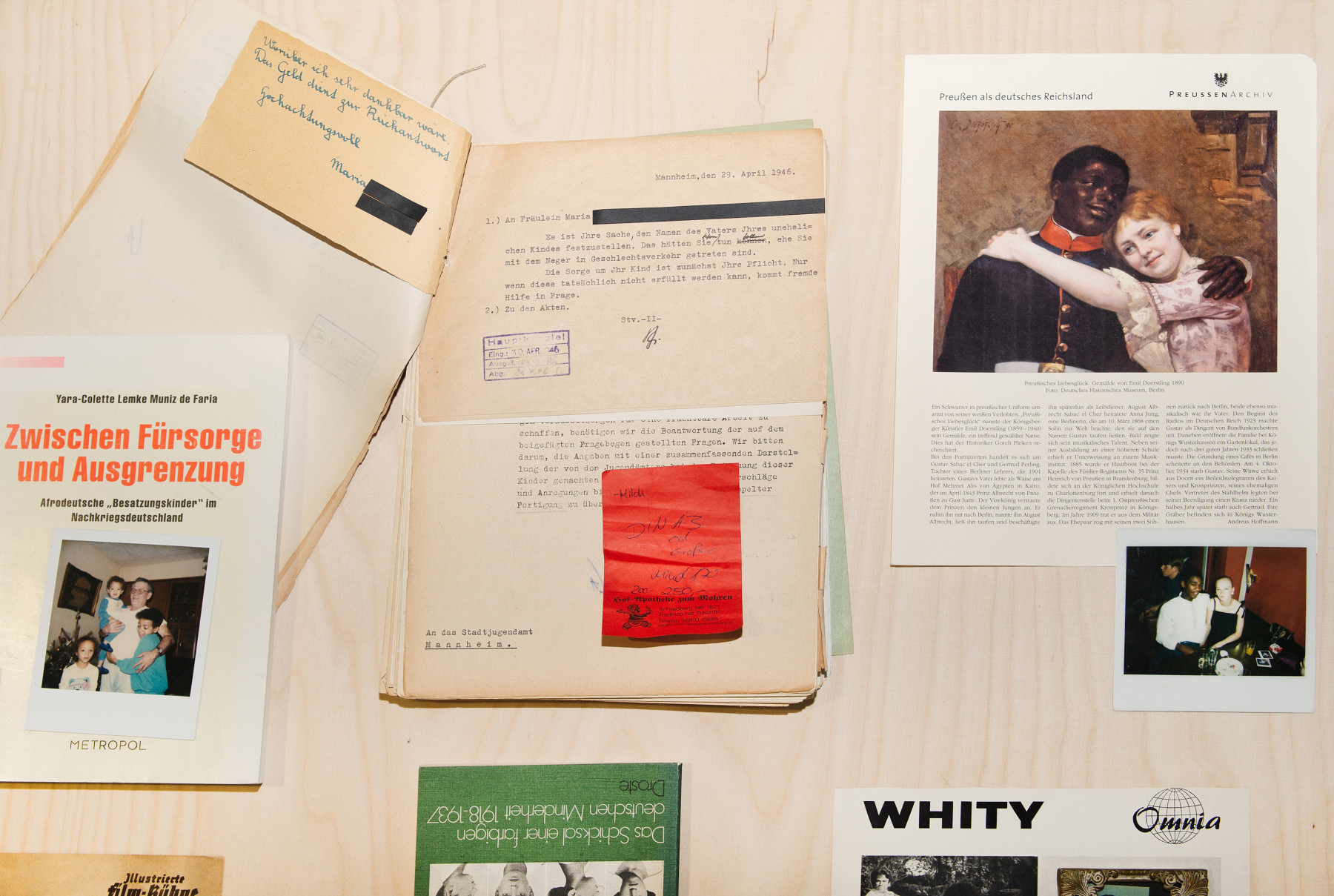

James Gregory Atkinson, Preußisches Liebesglück, 2021, Installation View (Detail) Dortmunder Kunstverein, 2021, Photo: Jens Franke

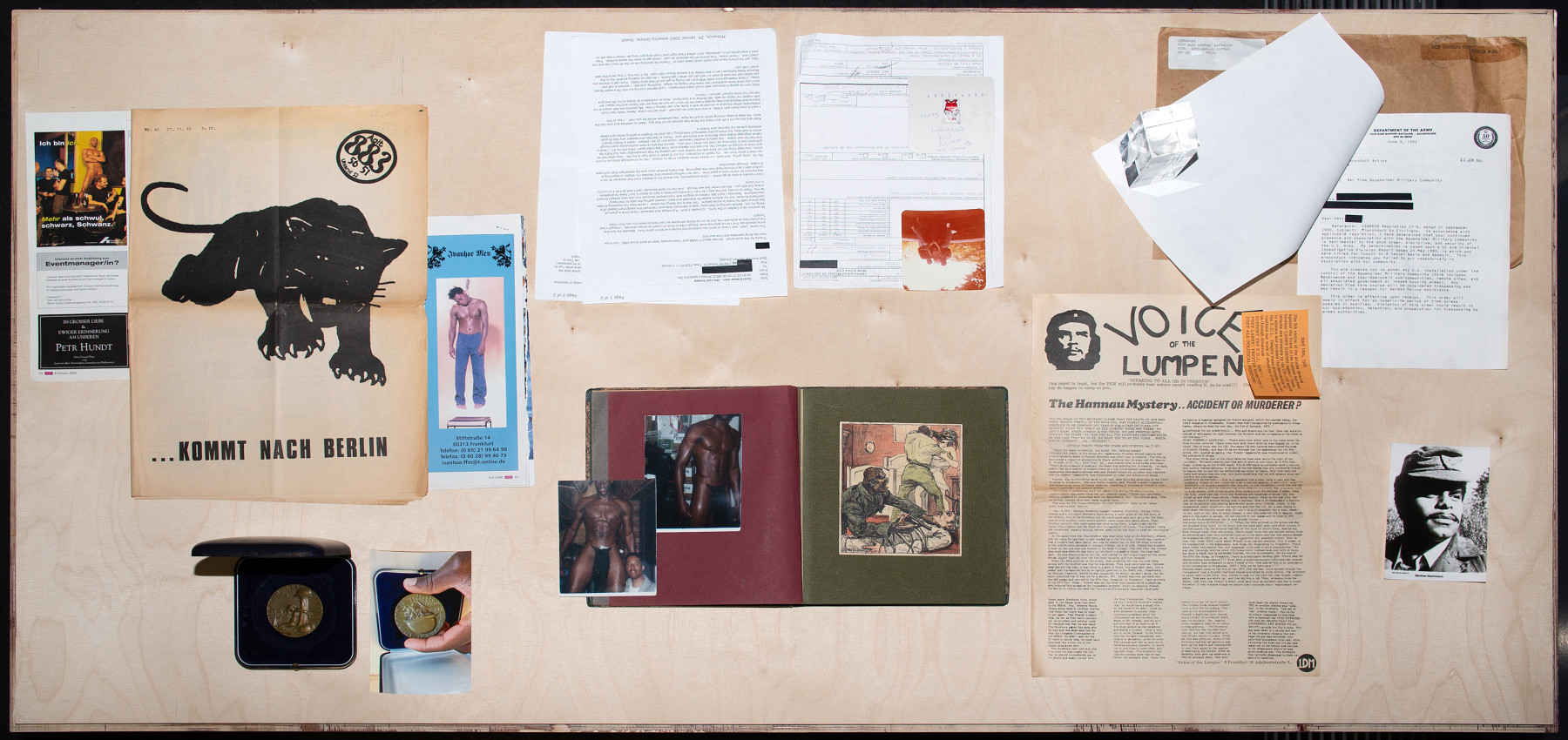

The exhibition opens with Preußisches Liebesglück (2021) – an installation looking at the long history of Black soldiers in Germany dating back to the Prussian Empire. A framed picture of Gustav Sabac el Cher hangs on the wall. His father, August Albrecht Sabac el Cher, was a Sudanese orphan gifted to the Prussian prince Albrecht by Muhammad Al in March 1843. He was one of the first members of the African diaspora to attempt social integration in Germany. Born to a white mother, his son Gustav Sabac el Cher grew to be a member of the German military and was a conductor with the Grenadier Regiment. He also composed music and arranged various Mozart overtures for military music. Next to it, a peacock-shaped woven wicker chair is flanked by amateur photographs of peacocks. Referencing Black Panther Huey Newton's famous photo from 1967, the works carry a sense of masculinity or questioned masculinity that traverses the entire exhibition.

James Gregory Atkinson, Preußisches Liebesglück, 2021, Installation View (Detail) Dortmunder Kunstverein, 2021, Photo: Jens Franke

In front of the chair, a blown-up postcard from a German propaganda campaign against Black people from the 1920s titled “Die schwarze Schmach”, loosely translated as the black shame. The racist campaign, which originated in Germany and gained international awareness, targeted the deployment of troops from the French colonies in Africa during the Allied occupation of the Rhineland. In stark black and white, we see a racialised caricature of an African man dressed in a French uniform carrying a gun while White workers dig on the ground below. This scene displays a reversal of power – the domination by the Black and submission of the white. The campaign aligned the trauma of the forfeiture of World War I to the French forces and the subsequent loss of German national identity to this Black presence, inflaming populist sentiment driven by wild tales of mass acts of violence against white women and children.

James Gregory Atkinson, Installation View, Dortmunder Kunstverein, 2021, Photo: Jens Franke

In an audio recording, one can listen to a Bundestag's debate from 1952 regarding the status of “Uneheliche Kinder der Besatzungsangehörigen”– children born to foreign national soldiers stationed in Germany after the end of World War II. In their “Antrag”, the members of the Social Democratic Party, the SPD, called for alimony to be collected from the biological fathers to support the German mothers and their children's situation. SPD party member Frieda Nadig declares that “...educators, the public, and the press have a great task here: to prevent, by their opinions, the resurrection of old doctrinaire thoughts of racial mania.” Yet, throughout the debate, the main word associated with children of African-American soldiers and their German mothers is “problem”. In the aftermath of the horrors of the Nazis and fascist racial manias, campaigns directed against African Americans and their children took hold in Germany with a virulence emphasised by the exhibition's collected archival material.

James Gregory Atkinson, Zeitkapsel Whity, Installationsansicht Dortmunder Kunstverein, 2021, Photo: Jens Franke

6 Friedberg-Chicago weaves together the realities of different family histories. Their differing circumstances are separated only by time. This becomes particularly evident when approaching a series of vitrines, encapsulating a series of non-linear material assembled by art historian Mearg Negusse and sociologist Eric Otieno Sumba together with the artist. For example, a photograph of Atkinson’s parents, taken during a party at the nightclub Central Studio in Friedberg, is placed next to Gustav Sabac el Cher and his German wife, accompanied by detailed information about Savac el Cher’s military and biographical history. Further personal notes and mementoes intersperse with archival materials. A letter to the artist’s father in Chicago is juxtaposed with a power adapter from the early 1980s. This gesture of placing personal objects and ephemera alongside historical documents reveals how the African-American experience overlaps and clashes with German histories and realities. Books such as Zwischen Fürsorge und Ausgrenzung: ‘Besatzungskinder’ im Nachkriegsdeutschland (Between Care and Exclusion: 'Occupation Children' in Postwar Germany) by Yara-Collette Lemke Muniz are paired with the artist’s private family photographs of his siblings and grandparents. Across the different vitrines, the viewer is continuously confronted by bluntly racist comments, such as the worries of one reporter, who writes around the time of the debate at the Bundestag: “what a setback the first enrollment of these children will have on the German majority of the class.” Other displays include the magazine Voice of the Lumpen – a magazine by Black soldiers stationed in Germany fighting segregation in the United States. Paradoxically, in post-war Europe, black soldiers were granted more rights and freedoms than in their home country.

James Gregory Atkinson, Zeitkapsel Whity, Installationsansicht Dortmunder Kunstverein, 2021, Photo: Jens Franke

Atkinson’s new film 6 Friedberg-Chicago (2021) is displayed at the end of a long corridor. The film portrays a group of young men from Friedberg, descendants of African-American soldiers stationed in Germany, filmed within the unique architecture of the Ray Barracks. Choreographed by Josh Johnson, a community of moving and dancing bodies interacts with the buildings and surroundings. In time, a sense of complicity emerges. Individual movements become one, tied in time. Their formation is accompanied by the song Toxi Lied – Ich möchte so gern nach Hause geh’n sung by harpist and singer Ahya Simone, pointing towards the contradictory notions of home for these young men. Initially performed in 1952 by Leila Negra (birth name Marie Nejar) for the film Toxi, the song, like the film, centred around a child of a Black occupation soldier and white German woman. Following her mother's death, a German family adopts the child. At Christmas, her father picks up his child and takes her with him to the US, rendering all problems solved. Similar narratives were a harsh reality for many children after World War II, as German mothers were advised to give their children up for adoption to secure a better and more natural environment for them to grow up in.

James Gregory Atkinson, 6 Friedberg-Chicago, 2021, film-still. Courtesy: the artist.

The young men are brought together through a shared history that goes beyond the barracks in Friedberg. As the clocks from the entrance, the film uses the hybridity of time and place to convey a narrative that consists of a complex history, identities, spaces, different counties and centuries, and remnants of the two World Wars. As historically imbued as the exhibition is, with the vast and vital archive at its core, the clocks, like the film at the end, also function as pointers to a moment of now, the present moment. As the clocks tick, they mark parallels and dissonances, distance and unison—a connection beyond the time of Friedberg and Chicago.

James Gregory Atkinson - 6 Friedberg-Chicago

11.12.2021 - 13.03.2022

Dortmunder Kunstverein

Park der Partnerstädte 2

44137, Dortmund